The Scale War Beyond Tariffs

Why economic dominance hinges on mastering both production and consumption scale

Most commentaries on the U.S.-China trade war focuses narrowly on tariffs, deficits, or decoupling. But these are symptom, not the root causes. At the core of the issue is scale. It is a contest to build and sustain the most comprehensive system of production and consumption at the same time. Long-term leverage depends on the ability to command both sides of this economic equation.

At first glance, the U.S. tariff escalation appears to serve two practical objectives: reducing the trade deficit and weakening China’s manufacturing dominance, especially in strategic sectors.

During the first wave of Trump-era tariffs, I spoke with several Chinese manufacturing owners who explained to me how fragile industry margins are. Average profit margin barely reaches 10%. At 30% tariff rate, factories can barely stay afloat by using a combination of creative tactics, including shipping goods in de minimis parcels which are duty free, finishing assembly in 3rd country hubs, and splitting the added costs with clients, all while trying to avoid passing excessive expenses on to end consumers. Beyond that threshold the supply chain unravels. At 150%, tariff becomes a de facto embargo, one which we can only assume is used as negotiation tactics to force Beijing into concessions.

Moving beyond intent, let’s now examine whether these tariff objectives are achievable in practice.

The Structural Trade Gap: Reserve Currency Trap and Fiscal Imbalance

Rather than viewing trade deficits through a reflexive mercantilist lens, modern macroeconomics explains persistent trade gaps through a national accounting lens:

Trade balance = National saving - Domestic investment1.

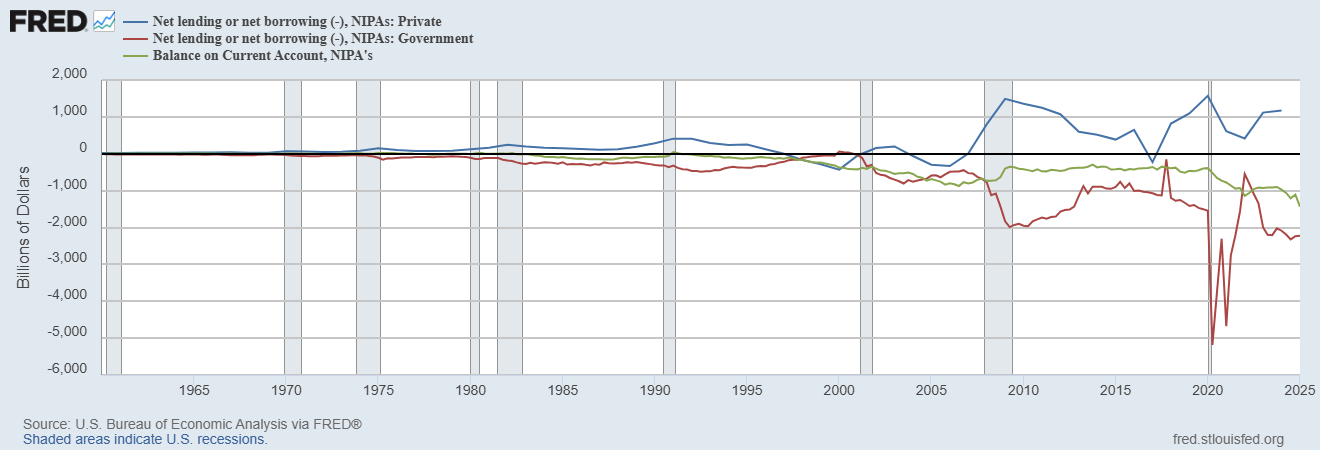

The FRED chart below plots the accounting relationship in practice. The green line tracks the U.S. current-account balance. The blue line shows net lending (saving - investment) for the private sector while the red line shows net lending for the government. Add the blue and red lines together, you obtain the green line almost year for year, visually confirming that the external trade balance is nothing more than the mirror image of the combined saving-investment gaps of households, firms, and the public budget.

When a country saves less than it invests, it must import the difference in the form of foreign goods and capital. The United States runs the world’s largest capital markets and issues the reserve currency, so global investors constantly recycle their excess savings into dollar assets in the forms of U.S. Treasuries, equities and real estates. Those capital inflows finance domestic investment that exceeds America’s meager household savings and, by arithmetic, require a goods-and-services deficit. In other words, the U.S. imports because the rest of the world chooses to save in dollars.

At the same time, U.S. tech giants like Apple, Google, and Meta extract global income without proportional domestic reinvestment, supercharging consumption while the manufacturing backbone weakens. The result is a structural setup where the U.S. runs on imported goods and exported financial assets.

No tariff can reverse that equation unless policymakers tackle the deeper architecture of global capital flows.

Global Supply Chains Are Shifting, Not Departing From China

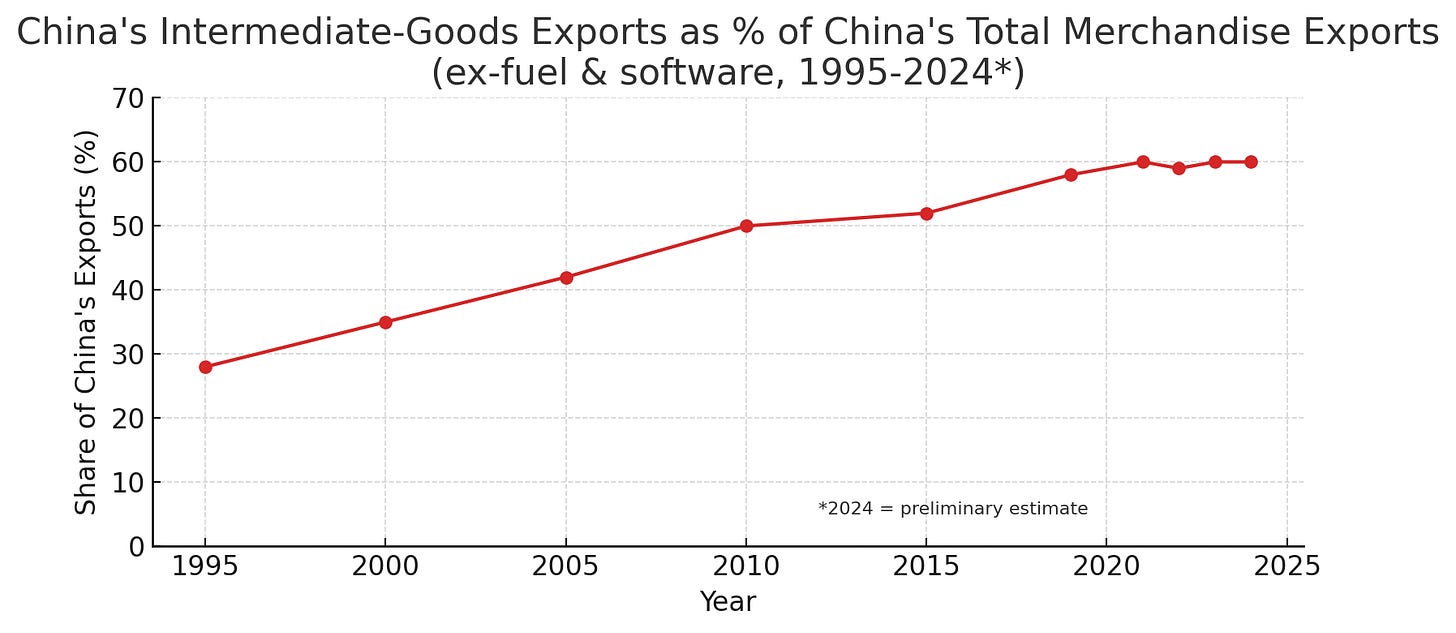

Over the past decade, some final assembly stages have migrated to a range of alternative manufacturing hubs across Southeast Asia, India, Eastern Europe and Latin America. Yet the industrial backbone, which Figure 2 shows now generates almost 60% of China’s export value in the form of intermediate goods, remains rooted in China’s coastal clusters.

Apple offers a clear example. While 20% iPhone assembly now occurs in India2, core sub-assemblies such as camera modules from O-Film, lens units from Sunny Optical, printed circuit boards from Foxconn, and battery packs from Desay are all produced by Chinese suppliers and then shipped to the final assembly plants. By contrast, newer facilities in India or Vietnam handle limited enclosure fitting, software flashing, and packaging due to their thinner supplier networks and tooling capacity3.

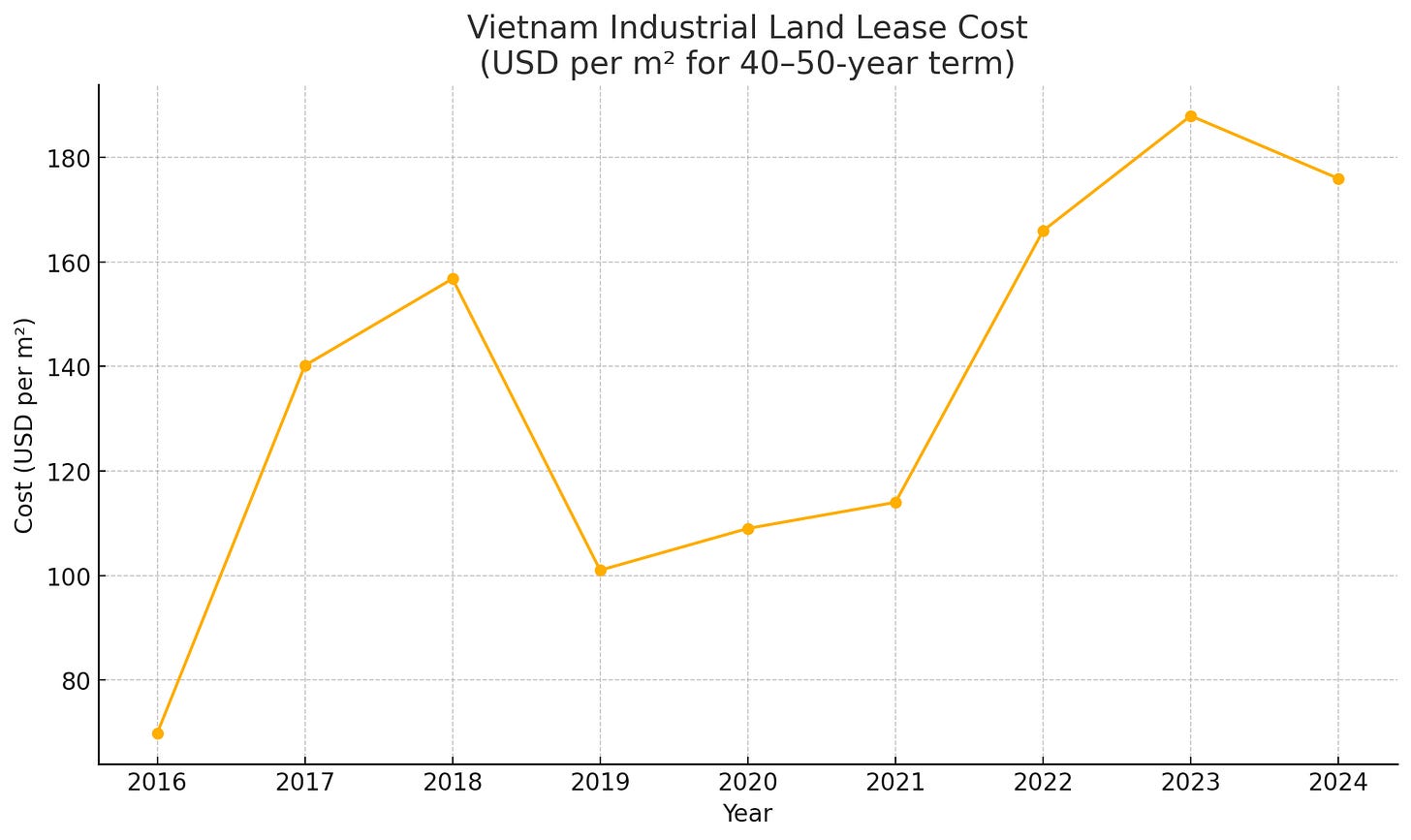

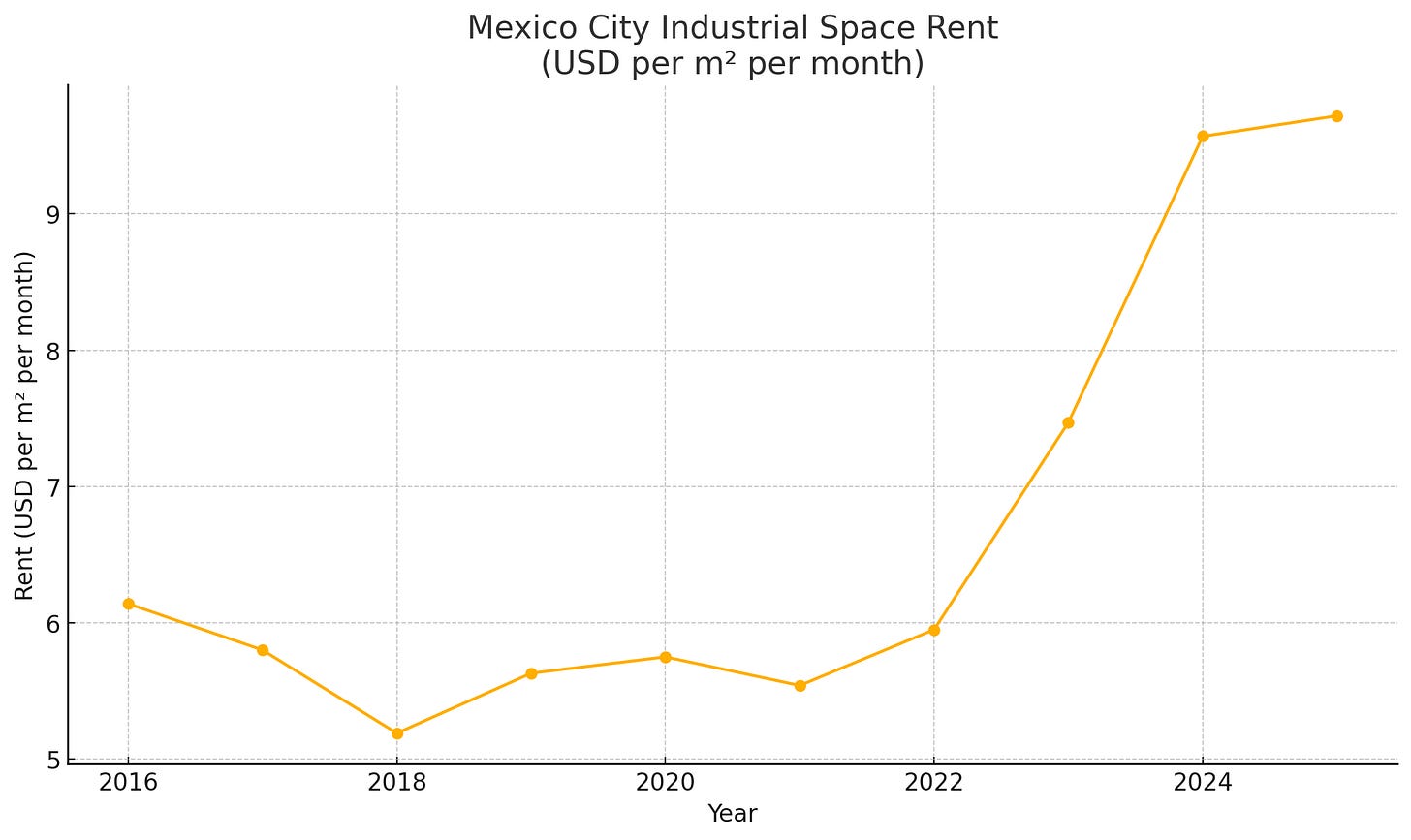

The spillover of China’s final assembly work to other countries has already stretched local capacity and driven up cost factors. Recent industrial rent data shows the pressure on alternative hubs. In Mexico City, monthly warehouse rents jumped 70% in just three years. In Vietnam, industrial land lease prices in key manufacturing corridors rose nearly 3x above 2016 level. Both jumps greatly exceeded local inflation, underscoring the disproportionate cost pressure created by even limited relocation.

So-called decoupling has been modular. Final touches relocate but upstream concentration stays put. Tariffs raise costs along the value chain and inspire partial rerouting, yet they cannot erase two decades of accumulated industrial depth across sectors.

Scale After the Trade War

The contest pits China’s production scale against America’s consumption scale. The country that unites both levers of scale will win.

China’s advantage lies in unparalleled manufacturing clusters that cut costs through volume and speed driven by proximity.

America’s advantage lies in the world’s biggest consumer market which is supported by reserve currency liquidity along with cultural and technological soft power.

Tariffs may buy time, yet integration rather than isolation decides the outcome. The nation that rebuilds its missing half faster will lock in the next hegemonic cycle.

Scale cannot grow out of trade barriers alone. Policymakers must build it through industrial depth and a sustainable financial base that does not rely on permanent foreign borrowing.

Beijing’s Countermove: Domestic Demand as a Second Engine

Aware of its dependence on external demand, Beijing codified a “dual circulation” (内循环/外循环) 12 year blueprint4. The plan aims to boost domestic consumption through:

expanding social safety nets, especially for the vulnerable groups such as seniors and unemployed urban residents, thereby lifting basic consumption ability

cutting social security contributions which are regressive and weigh most heavily on low-income groups to boost disposable incomes

advancing the “invest in people” agenda5 set out in the Government Work Report this year by creating a centrally funded cradle-to-college subsidy covering childbirth and education costs for children aged 0-18, a policy that stimulates consumption in the short run and builds human capital in the long run.

China’s path is not friction free. Local governments are weighed down by a swelling municipal bond debt pile. Estimates show the burden is well above $6 -8 trillion6 that ballooned during the real estate bubble. This overhang constrains their capacity to fund new social welfare programs.

Without coordinated reform of fiscal and welfare policies, household consumption may still lag industrial output, perpetuating excess capacity and deflationary pressure. Nevertheless, Beijing is accelerating its push to bolt a demand engine onto its existing production colossus.

Washington’s Dilemma: Fiscal Discipline and Long-Cycle Investment Without Weakening Demand

Because the trade gap mirrors America’s saving - investment shortfall, lifting national saving is the only durable fix. This agenda requires

fiscal restraint that reduces federal deficits and raises public saving, and

redirection of capital into long-cycle infrastructure projects such as energy security, semiconductor fabs, and workforce development instead of into pure consumption subsidies.

Here lies the paradox. If policymakers cut deficit-driven spending too aggressively, they risk eroding the consumption scale that underpins U.S. leverage. A practical compromise is spending re-composition rather than outright austerity. The government can keep purchasing power intact and still channel incremental outlays toward capacity-building investments.

If Washington relies on tariffs without fiscal realignment and industrial investment, it faces stagflation. Supply shocks raise prices, real wages stagnate, and inflation arrives without industrial recovery.

The Future Belongs to the System That Masters Both Scales

Stephen Miran argues for a tariff-based strategy that ties trade enforcement to currency realignment. He argues that by imposing tariffs the United States can pressure trading partners into re‑valuing their currencies, and therefore making American exports more competitive without larger fiscal sacrifices at home. The idea is elegant: tariffs shoulder most of the work and a stronger RMB closes the gap, but history cuts against it. After the 2018–19 tariff rounds, the U.S. goods deficit with China widened from roughly $420 billion to $435 billion7 even as average tariff rates jumped more than six‑fold. Miran’s framework is tactically provocative but strategically thin. It overlooks three structural hurdles: first, the combination of reserve currency inflows and persistent U.S. fiscal deficits that perpetually reopen the trade gaps. Second, the practical difficulty of untangling supply chains still deeply embedded in China despite higher tariffs. Third, the hard truth that decades-old industrial shortfalls cannot be fixed by market incentives alone.

The real challenge is building a new economic architecture—one where production and consumption scale are mutually reinforcing.

The new world order won’t be determined by headline tariff rates or one‑off trade balances. It will be defined by who builds the most irreplaceable system of scale that’s anchored by industrial depth and a sustainable financial base that does not depend on perpetual foreign borrowing. For the United States, that means aligning monetary policy, fiscal tools, and industrial planning around resilience, not just GDP optics.

The trade (current‑account) balance equals national saving minus domestic investment; see IMF, BPM6, §2.4.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-04-10/apple-s-india-iphone-output-hits-14-billion-in-pivot-from-china

https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/apples-supply-chain-economic-and-geopolitical-implications/

https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2023/content_5736706.htm

http://theory.people.com.cn/n1/2025/0318/c40531-40441102.html

https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Markets/China-debt-crunch/China-s-hidden-debt-problem-bigger-than-Beijing-suggests-analysts-say

https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/highlights/annual.html