At a time when coffee costs $6 and even cup noodles have seen price hikes, a few products have managed to hold their prices steady for decades. Costco’s $1.50 hot dog is perhaps the best-known case, maintained at that price only because it is intentionally sold at a loss to bring people through the door. AriZona Iced Tea is another long-standing example, holding its 99¢ price tag since the 1990s through tight vertical integration to the point that the company even owns its own rail lines for sugar deliveries, yet now facing the prospect of raising prices for the first time in almost 30 years.

Then there is the humble disposable lighter, a product that has quietly defied inflation for the last 20 years without subsidies, without marketing gimmicks, and without the cushion of higher-margin products to offset costs. In China, it still sells for just ¥1. In the U.S., you will find it at liquor stores for a buck. In Europe, one euro. Despite two decades of inflation, commodity shocks, and rising labor costs, the price tag hasn’t budged. It is as if time and inflation forgot this object entirely.

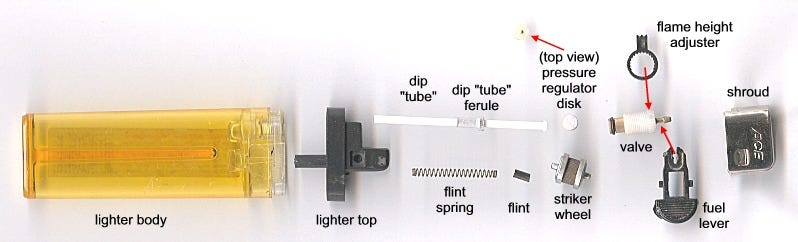

At first glance, it's easy to dismiss the humble lighter as a simple commodity churned out by cheap labor. It's lightweight, ubiquitous, and seemingly low tech. But this is a surprisingly complex object. It goes through 12 production processes, involves up to 30 subcomponents, and must meet 15 testing standards. Its manufacturing process spans over a dozen techniques, including injection molding, stamping, bending, electroplating, and spraying.

Shaodong: From Scrappy Town to Global Lighter Capital

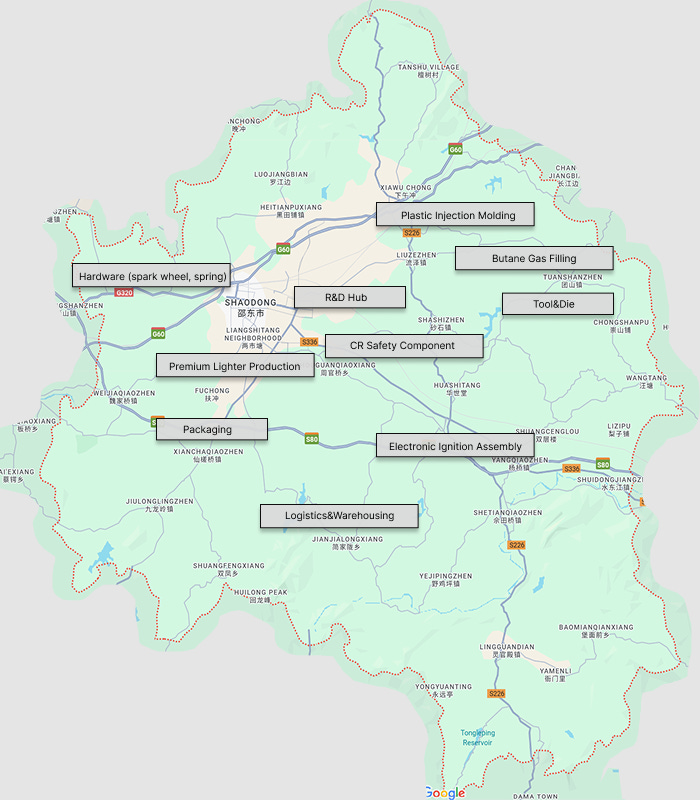

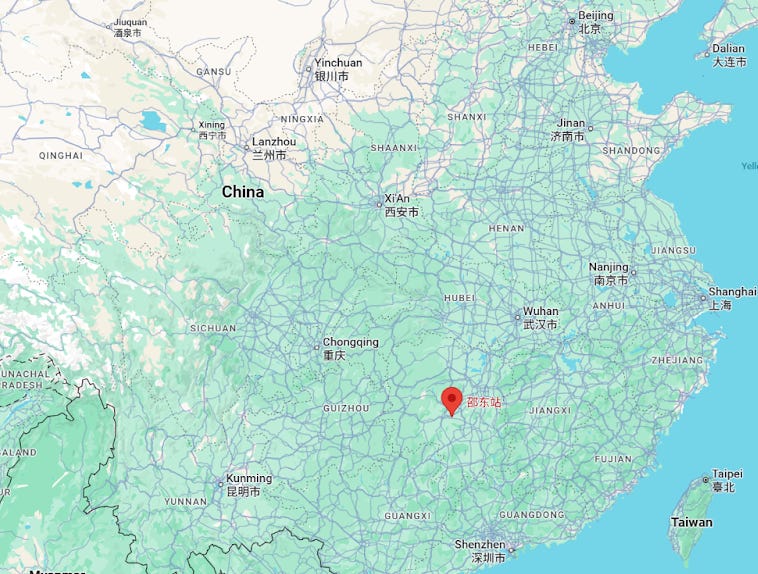

Each year, 20 billion lighters are sold around the world. Roughly 70 percent1 come from an unexpected location: Shaodong, a county-level city tucked in the middle of nowhere in central China's Hunan Province.

Shaodong’s geography was never its strength. Though similar in size to the City of Los Angeles, over 80 percent of the area is covered in hills and mountains. Just 10 percent of its area is flat enough for farming or industrial use. Arable land per person ranks among the lowest in Hunan Province2. With limited natural resources, survival depended on adaptation rather than abundance.

That necessity bred ambition. In the 1990s, rural households began converting their homes into workshops. The first wave of entrepreneurs sold buttons, combs, and small hardware across rural markets.

The rise of lighter manufacturing built on this momentum. It started with scattered, low-tech workshops and grew into a manufacturing system that is now known as the world’s lighter capital.

How that transformation unfolded, and how the price remained unchanged for 20 years, reveals a story of innovation through relentless optimization, industrial resilience built on long-term planning, and effective coordination between local government and private enterprises.

Relentless Optimization Through Automation

In the early 2000s, most lighter factories in Shaodong operated in a rudimentary, labor-intensive fashion. Many rural households lived upstairs while downstairs doubled as small workshops. Locals would take home parts to assemble by hand, earning a few dozen yuan a day. This household-based production model formed the backbone of the local ecosystem.

Larger firms, like Dongyi Electric, formalized this model. At its peak, Dongyi employed 14,000 workers, all seated in rows manually assembling lighters. But despite greater scale, labor still accounted for the bulk of operational cost3.

At the time, monthly wages hovered around ¥1,000 ($140), which made such practices viable. But the economic environment shifted quickly. Over the next decade, wages rose sharply, surpassing ¥4,000 ($560) per month4.

At the same time, the price of a disposable lighter was effectively fixed. As a highly price-sensitive product sold mostly in convenience stores and tobacco shops, even small increases risked losing volume. This rigid price became an invisible constraint on the entire production system. With each unit earning only ¥0.02 ($0.003) to ¥0.04 ($0.006) in profit, labor costs had to remain under 7% to stay afloat. The math no longer worked. Yet even with higher pay, attracting enough workers to a mountainous town with limited infrastructure remained difficult.

Faced with low productivity, high labor costs, and increasing difficulty in hiring, Shaodong’s light manufacturers, led by Dongyi Electric, began shifting toward automation. Dongyi began investing ¥40 million ($5.6 million) every year into its own R&D, and upgrading automation equipment. Engineers tested conveyor belt speeds, machine sequences, and modular tooling. By integrating automation into the final assembly line, they cut 80 percent of the workforce, increased daily output by ninefold, and reduced unit labor cost by 85 percent5.

This marked the beginning of Shaodong's relentless pursuit of optimization. Labor scarcity was no longer seen as a constraint but rather treated as an engineering challenge.

Institutional Support For Design Capability

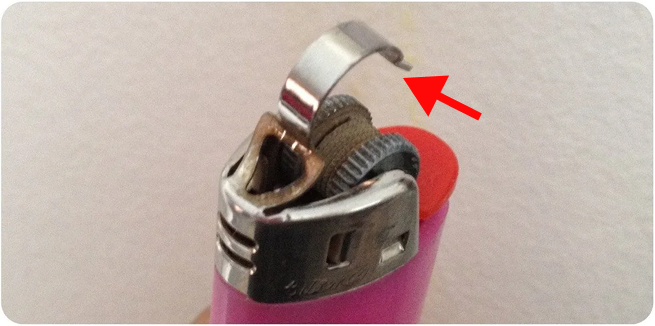

Just as automation gained ground, U.S. regulators imposed a new barrier. In 1997, the Child Resistance (CR) regulation was introduced, requiring all lighters under $2 to include a child safety lock. The rule was heavily lobbied for by leading Western players such as BIC and the Lighter Association of America, who sought to raise the compliance bar in ways that favored firms already holding key patents. The regulation's pricing threshold was carefully calibrated to capture nearly all of the Chinese-made lighters without touching premium U.S. products.

The rule had teeth. Western companies had already patented the dominant CR designs. To remain in the U.S. market, Chinese firms faced two options: pay high licensing fees, which would erase their already thin margins, or stop exporting entirely while scrambling to develop an alternative solution.

At the time, most of Shaodong’s factories had little or no in-house R&D capability. Their model was based on replication, not invention.

Recognizing this limitation, the local government and leading enterprises collaborated to establish the Shaodong Intelligent Manufacturing Technology Research Institute (known as “Shao Zhi Yuan”). With ¥200 million ($28 million) in initial funding, the institute offered R&D, automation consulting, shared testing labs, and most critically, support for developing original patents6. The institute fostered informal knowledge sharing across companies and created a collaborative ecosystem where best practices, tooling insights, and process learnings were shared among participating firms. This helped Shaodong shift from imitation to innovation, strengthening its position based on original engineering.

One of the clearest breakthroughs came in the development of the spark wheel, a tiny serrated steel disc that ignites the gas when struck against flint. In 2006, the EU introduced ISO 9994, a standard requiring consistent flame height with strict tolerances. This regulation significantly raised the bar for lighter safety and precision, especially in components like the spark wheel and fuel valve. For Shaodong firms, compliance became essential for global market access, adding pressure to upgrade both product quality and underlying engineering.

Producing the spark wheel at scale with consistent tooth sharpness and spacing had long been a problem. Even minor defects could cause misfires or ignition failures. The process was both intricate and inefficient, historically requiring hundreds of steps and manual assembly of delicate pins and shafts.

Working with Shao Zhi Yuan, local companies tackled this bottleneck through tooling redesign. They reduced the process from over 100 steps to just two. This breakthrough dramatically lowered costs, improved consistency, and enabled the part to be mass produced with high reliability.

The gains didn’t stop there. Working with Shao Zhi Yuan, local firms also developed automated testing lines and adaptive gas valves that adjusted flow rates and pressure in real time. Before the upgrades, Shaodong factories deployed entire rooms of testers, up to 35 workers per line, tasked with manually igniting lighters to ensure flame height compliance. The process was time-consuming and error-prone.

A job that once required 300 workers could now be done with 40. Flame height rejection rates dropped to under 0.5%.

This shift reflected a broader strategic direction rooted in long-term capability building. It reflected a deliberate reorientation toward strategic self-sufficiency, made possible by strong institutional backing. The local government’s role in forming the Shao Zhi Yuan institute provided the foundation for this transformation. The initial scramble to overcome patent barriers and regulatory exclusion evolved into a coordinated, government-supported initiative to build long-term design and engineering capability. Shaodong’s ability to meet global standards through original engineering reflects how public-private coordination elevated the region from replication to innovation.

Local Supply Chain Cluster

A lighter may weigh less than .2 ounce, but it depends on dozens of precision-made subcomponents. Up to the early 2000s, many of these components were imported from Japan and South Korea, whose firms dominated small-part hardware and die making.

This fragmented supply chain came at a cost. Delays were frequent. Prices fluctuated. Logistics created friction.

The breakthrough came through horizontal clustering. As the market for complete lighter assemblies flourished, Shaodong’s hardworking entrepreneurs seized the opportunity to build out supporting industries. The rise in finished lighter sales directly spurred the growth of a modular supplier network that provided critical components and specialized services. Recognizing this potential, the local government helped coordinate land use, streamline approvals, and support infrastructure upgrades to facilitate clustering. Interconnected firms across neighboring towns began specializing in distinct stages of the production process. Over time, Shaodong cultivated a dense supplier ecosystem. Today, over 100 subcomponent firms are packed within a seven-mile radius. Each township in Shaodong focuses on a single task: one handles plastic injection molding, another makes spark wheels, others produce CR safety locks, print designs, or fill butane canisters7.

This fine-grained division of labor created a highly modular system. It allowed innovations to spread quickly across firms, reduced downtime, and ensured Shaodong’s production system could flex with demand. Same-day delivery of components became the norm, enabling just-in-time coordination across workshops and maintaining supply chain resilience even under pressure. Most importantly, it pushed cost control to its limits, transforming what was once a fragmented network into a tightly coordinated industrial cluster.

Conclusion

Shaodong’s story is not one of cheap labor, massive subsidies, or sheer luck. It reflects how constraint-driven innovation can emerge through close coordination between local government and private enterprises. Every obstacle, whether rising wages, foreign regulation, or technical bottlenecks, pushed the region to invest in long-term planning, industrial upgrading, and local supply chain clustering. As a result, cost control reached its most refined form. The one-yuan price tag is no longer just a price point. It has become a durable moat that is hard to replicate.

But Shaodong’s experience is far from unique. Across China, towns have grown around the mastery of one product and its surrounding supply chain. Yiwu specializes in socks, Xuchang in wigs, and Putian in shoes.

Cheap Made-in-China goods are often dismissed, but they deserve to be studied. Beneath the low sticker prices lie decades of optimization, specialization, and coordination. This ability to find growth under constraint appears to be a structural pattern. We are seeing similar playbooks emerge in more technologically advanced sectors like semiconductors, EV batteries, and even large language models.

The one-yuan lighter may seem trivial, but it captures a deeper lesson. As the U.S. looks to reshore manufacturing, we might pause to examine the ecosystem behind this one-yuan lighter. What kind of coordination, long-term capacity, and systems-level capability does it take to sustain a supply chain that is resilient, cost-efficient, and continuously optimized?

The next time you flick a lighter, consider what it took to keep the price still for 20 years.

Changsha Customs. “2022年湖南打火机出口额超25亿元.” General Administration of Customs of the People’s Republic of China, March 2, 2023. http://www.customs.gov.cn/changsha_customs/508916/508921/6509109/index.html

Shaodong Municipal Government. “自然环境 (Natural Environment).” Shaodong.gov.cn, August 2022. https://www.shaodong.gov.cn/shaodong/zrhj/202208/038e5d881f714f28899bda0b598d0fae.shtml

The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. “湖南邵东:打火机点亮‘中国制造’.” Gov.cn, December 2023. https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/difang/202312/content_6921833.htm

National Bureau of Statistics of China. “Average Wage of Employed Persons in Urban Units.” Stats.gov.cn, accessed August 2025. https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01&zb=A0A01&sj=2024

Hunan Provincial Government. “大县担当 | 邵东打火机每只1分钱利润的背后故事 (The story behind Shaodong lighters profiting just one cent each).” Hunan.gov.cn, April 15, 2025. https://www.hunan.gov.cn/hnyw/sy/hnyw1/202504/t20250415_33641454.html

Shaodong Municipal Government. “邵东智能制造技术研究院:赋能‘打火机之都’新质生产力.” Shaodong.gov.cn, March 2024. https://www.shaodong.gov.cn/shaodong/c115500/202403/7cb5f80852e54c55bfae6b31b5e0d54a.shtml.

Xinhua News Agency. “中国‘打火机之都’点燃全球市场 (‘China’s “Lighter Capital” Blazes Trail for Global Success’).” News.cn, December 4, 2024. http://www.news.cn/local/20241204/468e9f573e8d460d98987b20fc3871a1/c.html.

This is a phenomenal micro example of Chinese industrial policy at work. Thank you!

An allegory of China’s frontier model journey, perhaps?